Curating an Art Exhibition about Japanese Peace Constitution Article 9

The Constitution of Japan was essentially written by the U.S. Military officials from the General Headquarters (GHQ) during the Occupation of Japan. “Article 9” of the Japanese Constitution, known as the Peace Constitution (Heiwa Kenpo), renounces war and possession of potentially belligerent forces as a sovereign right of the nation.

ARTICLE 9. Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes.

In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

This unique provision in the peace clause of the Constitution, unlike any seen elsewhere, reflects the idealism of the American New Dealers. This constitution, well received by the Japanese people who experienced the bitterness of war, has not been altered for 60 years. But now, with political instability in Asia and an upsurge in nationalism, its very existence is being questioned.

Article 9 greatly helped Japan recover from war and indeed reshaped the country, and through this article Japan avoided direct confrontation with other countries. There have been no casualties of war for more than 60 years. Although Article 9 has kept Japan from direct involvement in wars, indirect involvement in conflicts has allowed Article 9 to support a twisted status quo. This unique situation has given artists the opportunity to discover a theme to tackle and express in their works. Numerous artists have grappled with issues such as post-war problems and identity problems; these works are also related to the issue of Article 9 and world peace.

The art exhibition “Into the Atomic Sunshine – Post-War Art under Japanese Peace Constitution Article 9,” mounted in a climate in which the Constitution is faced with possible revision, attempts to raise issues and increase awareness of the influence of the peace Constitution, which played such an important role in shaping post-war Japan , and the reaction toward it of post-war art.

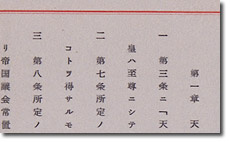

Outline of Constitutional Reform

8 February 1946 (Showa 21)

Papers of SATO Tatsuo, #22

National Diet Library

Alteration of the Constitution of the Empire of Japan to the Constitution of Japan after the Defeat

Just after the defeat, the Japanese Government expected that the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (so-called GHQ) would demand the revision of the Constitution of the Empire of Japan. On October 4, 1945, Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of GHQ, suggested an amendment of the constitution to Fumimaro Konoe, who was then Minister of State of the Higashikuninomiya Cabinet. Therefore, Konoe started to investigate the Constitution’s amendment. Parallel to this, Prime Minister Shidehara, who organized a new cabinet on October, 9 installed the Constitution Investigation Committee (so called Matsumoto Committee) led by Joji Matsumoto, the Minister of State, as a chairman, and began researching the constitutional amendment.

However, because of his war responsibility and being outside the Cabinet, there was a strong objection to the investigation of constitutional amendment by Konoe, and the matter came to a deadlock. The constitutional amendment work was given only to the Matsumoto committee, launched under a Shidehara cabinet. The Matsumoto committee was held from October 27, 1945 to February 2, 1946; it submitted “Private Plan of the Amendment of Constitution” on January 9, 1946.

“The MacArthur Draft” Has Been Secretly Developed

At first, GHQ was not going to interfere excessively in the amendment, but it then initiated an investigation of the Japanese constitution, especially focusing on a private constitutional amendment draft (“Draft Outline of the Constitution”) created by the Constitution Research Association (Kenpo Kenkyu Kai), from the beginning of 1946.

The concern inside of GHQ was MacArthur’s legal authority toward the Japanese constitutional amendment. On the issue of the Japanese Constitution, Courtney Whitney, who was the Senior Official of GHQ Government Section (Minsei Kyoku), submitted a report saying that any kind of steps, if MacArthur thinks they are suitable, need to be realized. This document suggests that after the launching of the Far East Committee, which included Soviet Union and Australia and which was approaching on February 26, the authority of MacArthur would not be unlimited.

In addition, on February 1, the day Whitney’s report was submitted, Mainichi Shimbun published a scoop regarding “the Matsumoto Committee Plan.” “The Matsumoto Committee Plan,” in this article, was comparatively liberal in the drafts submitted to the Matsumoto Committee; but Whitney analyzed the character of this plan as extremely conservative, and it did not get support by Japanese people. Therefore, GHQ judged that if it was assigned to the Japanese Government, world opinion, represented by the Far East Committee, might demand the abolition of the Emperor system. Therefore GHQ decided to create a draft.

On February 3, MacArthur established three principles to draft the Plan of Constitution of Japan on GHQ’s side—emperor as symbol of state and of the unity of people, renunciation of war, and sovereignty residing in the people—and gave this to Whitney. By receiving these three principles, GHQ Government Section created a committee to draft the constitution, and on February 4, Whitney ordered the drafting members that a constitution was the first priority and to draft it confidentially.

Among the twenty-five drafting members in the Government Section, four had experiences as lawyers, but none of them specialized in studying the constitution. Therefore, they referred to private Japanese constitution drafts such as the one written by the Constitution Research Association, and also constitutions of various other countries. An original plan was created from the tentative plans by working day and night at Government Section, and the draft was completed on February 12. On February 13, the “MacArthur Draft,” which was very liberal at that time, was submitted from the GHQ side to the Japanese Government.

Constitution of Japan (GHQ Draft)

13 February 1946

Papers of SATO Tatsuo, #31

National Diet Library

What is the “Atomic Sunshine” Conference?

The exhibition title “Atomic Sunshine” derives from a nickname given to the conference that created the new Constitution of Japan, which was attended by General Courtney Whitney of GHQ, Shigeru Yoshida (Prime Minister of Japan from 1947), Jiro Shirasu (translator), and Jyoji Matsumoto, the minister of the Department of State who was in charge of creating the new Japanese Constitution, on February 13, 1946.

The “MacArthur draft” presented to the Japanese Government on February 13 was an answer to the Matsumoto Committee Plan, which the Japanese Government had submitted on February 8. However, the Japanese side knew nothing of the drafting work done by GHQ, and were completely surprised by this “MacArthur Draft.”

General Whitney rejected Matsumoto’s conservative Constitution scheme, and explained that the GHQ’s version of the Japanese Constitution scheme was a definitive plan embodying Japan’s current needs for principles, and that it was already approved by General MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of GHQ. Then the American group came down to the garden of the palace and gave the Japanese group the time to read out the English version. While an American bomber flew overhead and shook the palace, the translator Jiro Shirasu came out to the garden and joined the American group. Whitney said to Shirasu,

“We have been enjoying your atomic sunshine.”

General Whitney’s comment made it clear to the Japanese who was the winner and loser of the war. He remarked that accepting the provisions stipulated in the GHQ draft would be the best way to keep the Emperor “secure,” and if the Japanese government did not accept this plan, then General MacArthur would propose this plan directly to the Japanese people. This conference creating the new Constitution later came to be called the “Atomic Sunshine Conference.”[1] Based on this GHQ plan, the Japanese cabinet created the amendment plan, and it was proclaimed as the new Japanese Constitution on November 3, 1946.

Outline of a Draft for a Revised Constitution

6 March 1946 (Showa 21)

Papers of SATO Tatsuo, #46

National Diet Library

Who proposed Article 9?

The new constitution including Article 9 was written substantially by the GHQ, but there are various opinions about where the idea of Article 9 came from, and two opinions among many are well-known. The first one is that it came from Douglas MacArthur, and the second is that it came from then prime minister Kijyuro Shidehara.

About the MacArthur theory, both MacArthur and the United States were concerned about the rearmament of Japan, so to avoid that, they included the clause of pacifism in the Constitution. The article of renunciation of war, stated in MacArthur’s three principles (also known as MacArthur Note), is as follows:

2. War as a sovereign right of the nation is abolished. Japan renounces it as an instrumentality for settling its disputes and even for preserving its own security. It relies upon the higher ideals which are now stirring the world for its defense and its protection. No Japanese army, navy, or air force will ever be authorized and no rights of belligerency will ever be conferred upon any Japanese force.[2][3]

However, on the side of the Shidehara theory, Prime Minister Shidehara visited MacArthur on January 24, just before the announcement of MacArthur’s three principles, and Michiko Hamuro, the daughter of Ohira, heard from her father what Shidehara talked about with Komatsuchi Odaira, the Privy Councilor, and regarding this conference, she wrote:

(Shidehara)said that starting from the idealistic position that the world should not maintain any military, to make a society without war we should renounce war itself. Then, MacArthur suddenly stood up, and grasped Shidehara’s hand with both hands, and, full of tears, he said, that is right. Shidehara was a little surprised by this. … MacArthur seemed to think about doing something good for Japan as much as possible, but some parts of the U.S. government, some members of GHQ, and also the Far East committee began an argument that had a tremendous disadvantage for Japan. Countries such as the Soviet Union, Holland, and Australia feared the institution of the Emperor itself. … Therefore, they insisted that to abolish emperor system, the Emperor needed to be judged as a war criminal. MacArthur seems to have been troubled about this very much.

Therefore MacArthur thought that the idealism of Shidehara, the announcement of renunciation of war, need to be done as soon as possible, and show that Japanese people do not cause war in the world and get trusts of foreign countries, and clearly define that Emperor is a symbol of Japan in the constitution, so we can start to keep Emperor system without the interference of various countries. … Both of them agreed that there is no other method to keep Emperor System in Japan, so Shidehara made up his mind to accept this draft.[4]

In addition, MacArthur tells in his autobiography Reminiscences (1964) that the article of war renunciation was suggested by Shidehara[5], supporting the opinion that Article 9 was proposed by Prime Minister Shidehara. However, Shigeru Yoshida, who became the prime minister after Shidehara, denied this theory in the book The Yoshida Memoirs (1957), and mentioned that General MacArthur had declared his intentions earlier than Shidehara.

Function of Article 9 in the Postwar Period

Considering post-war Japan, maintaining Article 9 led Japan to economic prosperity. However, the process was complicated.

In 1951, Japan became independent of the occupation by the U.S. at the Treaty of Peace with Japan in San Francisco. Although the Republic of China participated, People’s Republic of China, Republic of Korea, and Democratic People’s Republic of Korea did not, and this became a huge war responsibility problem in post-war Japan. However, the message of Article 9, that Japan ”renounces war,” also had a meaning of apology toward the Asian countries which Japan had invaded.

On the same day of the peace treaty, Japan and the United States concluded the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty (later it became Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan). Since then, the situation of Article 9 has been part of an even more twisted status quo; Article 9 sustains the presence of the U.S. military in Japan. This is the reason why the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty and Article 9 are often discussed together.

Furthermore, after the outbreak of the Korean War and the drastic change of American policy concerning Japanese democratization and non-militarization (the so-called reverse course), Japan started to organize the National Police Reserve in 1950, which became the National Safety Force in 1952 and the Self Defense Force in 1954. Furthermore, when Nixon visited Japan in 1953, he mentioned that Article 9 was a mistake, and Japan should revise the constitution.

To oppose the reverse course of conservative government and revision of the constitution, in 1951, under the policy of “protection of the Constitution and anti Japan-U.S. security treaty,” both the right and left wings of Socialist Party Japan were united and became the biggest political party in Japan. At the request of financiers who felt the crisis by the unification of the Socialist Party Japan, two existing parties, the Democratic Party of Japan and the Liberal Party united, forming the Liberal Democratic Party. Since then, the two-party system of the Liberal Democratic Party, advocating “revision of the Constitution / conservative / protection of Japan-U.S. security treaty”, and the Socialist Party Japan, advocating “protection of the Constitution / innovation / anti Japan-U.S. security treaty” were formed (the so-called 55 year system), and it lasted until 1993.

Furthermore, during the wars in Korea and Vietnam, built on Cold War underpinnings, Japan received economic benefits for its indirect cooperation with the U.S., all the while maintaining Article 9 and avoiding dispatching troops. However, mainland Japan and Okinawa were criticized both from inside and outside the country for collusion with the U.S. by maintaining U.S. military bases. Inside Japan, a brutal demonstration and struggle against the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty has grown.

In addition, during the Gulf War, the Japanese posture of refusing the dispatch of troops to the PKO because of Article 9 has been criticized both from inside and outside Japan. At the same time, Japan created an extremely rare economic development model, in that while it became a world economic power, Article 9 ensured that the military industry was not enlarged.

However, what I want to carefully contemplate is the “otherness” that Article 9 itself contains. Although the Japanese constitution possesses a viewpoint of a post-WWII constitution, expressed in its negation of the absolutization of national sovereignty and internationalization of the constitution, these have been considered in extremely nation-centered terms, such as the viewpoint of the state’s confrontation with other states. The definition of the Japanese nation was done by the U.S. occupation military, and the message of Article 9 was directed toward the Asian countries that Japan had invaded.

Therefore, I want to think this issue as a global issue, not as a Japanese domestic issue. What does it mean to include “renunciation of war” in one’s own constitution, and to appeal this way toward the others?

About the Definition of European States that Caused World War II

Nation-states were created during the modernization in Europe after the Napoleonic Wars, and constitutions have been used to define nationality—in other words, to regulate the nation. Furthermore, the idea of nation-state resulted in the idea of colonialism, and through this, it has been exported to Asia.

About the concept of the state, Max Weber reflected that the idea of the state should be defined by its use of violence.[6] Weber places the political group that monopolized the “means” of using the violence as the “state,” and this state uses violence to consolidate the order. That is to say, domestic problems are judged as a crime under the authority of states, but Weber points out that the mechanism of monopolizing the use of violence was completed in the process of modernization.

In addition, Carl Schmitt states that in the political arena, the distinction of allies and enemy becomes a specific index,[7] and states that war is produced by the hostility of denying the existence of the others. In other words, war is caused by hostility. By denying the recognition of others outside of its own state, which monopolizes the use of violence—that is to say, the violence of the negation of others in the battle between the states, which as political groups monopolize violence, will result in war. Then, the process of modernism bound up with the nation-state completes the mechanism of using violence. Two world wars were an inevitable result.

World War II created Emmanuel Levinas’ philosophy of the “Other”

As a result of fascism, in which the war machine took over the state, Europe experienced the tragedy of the Holocaust; and to reconsider the violence of the negation of others, the philosophy of “others” represented by Emmanuel Levinas was born. Levinas’ philosophy of others was a post-war European philosophy, and as such can be created only by the person who experienced the violence of the Holocaust, which absolutely lacked the philosophy of the “other.” The importance of the philosophy of others is that it abolished the violent ontology of Heidegger and brought ethical questions into philosophy again.

Levinas writes that wisdom is to find the possibility of existence of war forever, and also that no one can be distant from war. He mentions that war, rather, destroys the identity of the “same.”

For the philosophical tradition the conflicts between the same and the other are resolved by theory where by the other is reduced to the same – or, concretely by the community of the State, where beneath anonymous power, though it be intelligible, the I rediscovers war in the tyrannic opposition it undergoes from the totality.[8]

Also Levinas points out that to “let him be,” a relationship of discourse is required, and a face-to-face approach, in conversation as “Justice.”[9]

Furthermore, Levinas continues, the exceptional presence of the “other” is inscribed in the ethical impossibility of killing him in which I stands.[10]

Between the I and what it lives from there does not extend the absolute distance that separates the same from the other. … The reversion of all the modes of being to the I, to the inevitable subjectivity constituting itself in the happiness of enjoyment, does not institute an absolute subjectivity, independent of the non-I.[11]

Levinas also says that the power of the “other” is an ethical thing from the beginning, and the asymmetric relationship with the “others” creates war. Peace must be my peace, in a relation that starts from an I and goes to the other, in desire and goodness.[12]

As a Problem of Modernism – The Historian’s Quarrel in Germany and the Yasukuni Shrine Dispute in Japan

In the post-war period, relating to violence and the “other,” there are two interesting historical facts. Germany in Europe and Japan in Asia, both the aggressor countries and the defeated countries, have similar large-scale disputes. One is “Historikerstreit (Historian’s Quarrrel)”—an argument whether the relativization of the Nazi regime can be possible or not, mainly represented by Jürgen Habermas and Ernst Nolte; and the other one is “Yasukuni Ronsou (Yasukuni Dispute)”—whether we can justify the worshipping of the Yasukuni Shrine, which honors the war dead (called Eirei) who devoted their lives for Japan, mainly represented by Tetsuya Takahashi and Norihiro Kato.

The “Historian’s Quarrel” started in the early summer of 1986 with Habermas’s criticism of two texts: Nolte’s lecture which was to be given in Frankfurt, and Andreas Hillgruber’s book Zweierlei Untergang (Two Kinds of Ruin).[13]

In particular, Nolte claimed that Auschwitz is rather a reaction toward the Russian Bolshevik revolution and its copy rather than traditional anti-Semitism, and such kind of tragedy was inevitable in history, and comparable to the Great Purge of Stalin, and the massacres of Pol Pot.[14] That is to say, his position is conservative: he interprets the crimes of the Nazis in a relative way, and tries to maintain the national pride of Germany.

Habarmas criticized Nolte as a revisionist, and claimed that the only patriotism that avoids the estrangement of West Germany from Western Europe is constitutional patriotism (German Constitution was also written by the United Nations); the loyalty to various universal principles of the constitution is now only what one is able to take pride in, unfortunately after and through Auschwitz, in Germany.[15]

Through this huge dispute, lots of questions had been raised: whether the historian is a leading figure of national identity; whether what Germans try to get is a constitutional patriotism that loves the constitution, or a national patriotism that loves the identity of the nation; whether history is abused for political disputes; and whether the education of history should be historicized or moralized.

Almost a decade after this dispute, the Yasukuni Dispute erupted in Japan. In the book Haisengo Ron (Theory of Post-War, 1999), Norihiro Kato insisted that in post-war Japan, the improvement of the constitution caused the “dissociated personality,” and as a result a “dissociation of the dead”—so by having a funeral for its own three million war-dead, then, Japan can build its own subject so as to make apology for the twenty million victims in invaded Asian countries.[16] Compared to this, in the book Sengo Sekinin Ron (Theory of Post-War Responsibility), Tetsuya Takahashi objected that not by considering Japan’s dead first, but only by maintaining the memory of the disgrace and continuing being ashamed—that is to say, considering the total responsibility of the war of aggression as a present problem—will the possibility of Japanese politics and ethics become realized.[17]

One thing to learn here is that both the Historian’s Quarrel and the Yasukuni Dispute are not solved by pure logic anymore. What Habarmas and Takahashi try to argue is a question of ethics and the “other,” as Levinas had discussed. Therefore, does the setting of the ethical question itself correspond to the face-to-face discourse with the “others”?

The Possibility of Article 9 in the 21st Century

Article 9 is the unprecedented declaration that the definition of the nation itself takes the existence of the “other” as a premise, thus overcoming the structure of modernism. The definition of Article 9, which defines the “Japanese” as a nation who “renounces war” was essentially written by idealistic American New Dealers—who are also the “other” for the Japanese. Then, the message of “renunciations of war” prompts discourses outside of “Japan,” namely to the “other”. In other words, the definition of the Japanese nation has a completely new form, and it has a global expanse.

The modern nation-state had tried to clarify the concept of hostility to prevent civil wars as a response to the Thirty Years War, and in it there also appears the constitution, the definition of the nation. However, in this era of globalization, to mark those outside the nation as hostile—in other words, to deny the existence of the “other” and create an enemy—is impossible. Not denying the existence of others and creating an enemy, but accepting the existence of the “other” and declaring “[we] forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation” in its own constitution, might allow the overcoming of modernism, which completes the mechanism of state as a political institution monopolizing the use of violence.

Article 9 is a declaration of the Japanese nation that “You” and “I” are “the same human beings,” and I do not attack the “other” who is the “the same human being.” This is an irreplaceable philosophy that overcomes European modernism, and will ground the possibility of making a 21st century without war.

The job of the artists is to express an ideal. As a person who engages for art, I want to think through the philosophy of Article 9, which is outside modernism, with Japanese, Americans, Asians, and all the people in the world. And at first, this exhibition starts with its own aim; mounted outside Japan, which is the “other” for Japan, because Article 9 is exercised in its communication with the “other”.

So, let’s step into the Atomic Sunshine, and deliberate. By reading a complex historical situation, and examine the influence of Article 9 on post-war art—the theme of this curatorial exhibition.

Shinya Watanabe is an independent curator based in New York. He acquired a MA at New York University and has traveled to 34 countries. His main focus has been the relationship of art and nation-state. He has curated numerous exhibitions such as Another Expo – Beyond the Nation-State, Action Painting Street Battle! Ushio Shinohara and Ryoga Katsuma. He is also a chair of Atomic Sunshine – Article 9 and Japan Exhibition Committee.

[1] “Overcoming Modernism” reminds us of the discussion led by members of the Kyoto School such as Kitaro Nishida in the magazine “Bungakukai (Literature World)” in 1942, and the slogans such as “Gozoku Kyowa (Five Races under One Union).” However, although I think the question of “Overcoming Modernism” is not itself mistaken, the real problem is that post-war Japan could not surmount the question of “Overcoming Modernism” as it was argued in 1942.

[1] In the book “Study of Shadows, Study of Windows,” Douglas C. Lummis comments on Whitney’s utterance “We have been enjoying your atomic sunshine.” “Whitney was trying to let Japanese people accept this new constitution, not only because this new constitution is excellent and theoretically demonstrated. This constitution draft is also evidenced by the power of atomic bomb, which is the biggest and most dreadful power in the world.”

[2] Toyoharu Konishi. Kenpo Oshituke Ron No Maboroshi [The Phantom of ‘Imposing’ the Constitution]. Kodansha Gendai Shinsho, 2006. P. 12-13

[3] In addition, the author, Shinya Watanabe, confirmed that the underlined part “Japan renounces it (war) as an instrumentality for settling its disputes and even for preserving its own security” was deleted by Charles Louis Kades, one of the main drafting members with Whitney, in process of drafting the constitution, by the testimony of Beate Sirota Gordon, the drafting member of Japanese Constitution.

[4] Kenpo Chosa Kai. Kenpo Seitei no Keika ni Kansuru Shouiinkai Dai 47 Kai Gijiroku. The Record of the 47th Conference of the Establishing Process of the Constitution]. Ohkurasho Insatukyoku, 1962

[5] About the question that MacArthur suggested Article 9 but mentioned that the Article 9 was created by Shidehara in his 1964 autobiography: in the book Two Thousand Days of MacArthur, Sodei Rinjiro states that because of the outbreak of the Korean War, MacArthur needed to change the principle of pacifism which he had written, so presented with this disgraceful situation, MacArthur might have tried to make Shidehara the creator of Article 9.

[6] Max Weber, Translated by Ikutaro Shimizu. Shakaigau no Konpon Gainen [Soziologische Grundbegriffe; Basic Concepts in Sociology] 1922 Iwanami Bunko, 1972. P88-89

[7] Carl Schmitt, Translated by Hiroshi Tanaka and Takeo Harada. Seijiteki namonono Gainen[Der Begriff des Politischen] Duncker & Humbolt. München, 1932 Miraisha, 1970 P14

[8] Emmanuel Levinas. Totality and Infinity Duquese University Press, Pittsburgh. 1969 P47

[9] Emmanuel Levinas. Totality and Infinity P71

[10] Emmanuel Levinas. Totality and Infinity P87

[11] Emmanuel Levinas. Totality and Infinity P143-144

[12] Emmanuel Levinas. Totality and Infinity P306

[13] Jürgen Habermas, Ernst Nolte and others. Translated by Kenichi Mishima and others. Sugisarou to Shinai Kako – Natizm to Doitu Rekisika Ronsou [“Historikerstreit”, Die Dokumentation der Kontroverse um die Einzigartigkeit der nationalsozialistischen Judenvernichtung] R. Piper GmbH &Co. München 1987. Jinbun Shoin, Kyoto. 1995

[14] “Historickerstreit” P9-34

[15] “Historickerstreit” P68

[16] Nirohiro Kato. Haisengo Ron [Theory of Post-War] Chikuma Bunko. Tokyo. 2005 P104-119

[17] Tetsuya Takahashi Sengo Sekinin Ron [Theory of Post-War Responsibility] Kodansha Gakujyutu Bunko. Tokyo. P210-219