IV. Conflicting Agendas

A. A Regional Exhibition Problem - The case of The Ballad of Kastriot Rexhepi by Mary

Kelly and Michael Nyman

a. An Article in the

On

Found sitting alone in a war field, the war orphan was brought to a hospital where nurses cared for him. Serbian nurses gave him a new name: Zoran, a popular Serbian heroic name. However, when the Serbs fled at the end of the war, ethnic Albanian nurses renamed this war orphan Lirim. This boy at 22 months old was reunited with his parents, and got his real name back--Kastriot.

Kastriotüfs mother Bukurie Rexhepi and family members had harrowing escapes. Amid NATO's air strikes and the Serbsüf ongoing effort to push out Kosovo Albanians, Serbian bombardment started in the first week of April around Kolic, the mountain village where Kastriot lived, located northeast of Pristina, the Kosovar capital. Serbian paramilitary troops arrived after the shelling, forcing Bukurie and her 28-year-old husband Afrim to join their relatives who decided to escape.

The weaker family members rode down the hill on a tractor- trailer, but Serbian police prevented them from reaching Pristina. Afrim, Bukurie, their son, two of Afrim's brothers, a cousin and his wife managed to walk the fifteen miles down the winding mountain road to Pristina. The biggest problem was the lack of food and water. Because of insufficient amount of food, the child grew weak. Then, according to family members, a fight broke out between the rebel Kosovo Liberation Army and Serbian paramilitaries. This incident sent them fleeing into the woods.

Sick with fear, Bukurie was unaware of what was happening to her child. Then, she looked down and realized that he didn't seem to be breathing. Both panicked parents tried to revive a pale and unconscious Kastriot. As the fighting and the sound of explosions intensified, Bukurie shook the boy harder and called his name, but he did not reply. Finally, she decided that he was dead. She covered his soft, pale face with kisses and laid his small body on the ground.

"I wish I would have been caught and had my throat cut before I would watch my child die in my hands," Bukurie said. "We cried. But we couldn't scream because we thought they would hear us." Swallowing her screams, Bukurie and the others disappeared into the forest, never looking back.[1]

It is unknown exactly when Kastriot was found and in what condition. The Serbian police officers who found him have probably left Kosovo. The Serbian nurses are gone too. But somehow, the police heard his cries or saw him toddling in the field, and he was brought to the hospital in Pristina sometime in mid-April. Since he did not speak at all, it was uncertain whether he was a Serb or an Albanian.

Meanwhile, Afrim, Bukurie and their relatives zigzagged across Kosovo, avoiding Serbian offensives. They said they talked about going back for the boy's body but never felt that they could do it safely.

Gradually, Serbs were fled by KLA soldiers. When the KLA soldiers moved on, they moved forward. Finally, Bukurie reunited with her husband and family about two weeks after NATO troops occupied Kosovo on June 12. Until then, she always thought about her baby.

As refugees returned from camps in Macedonia and Albania, and tales of wartime atrocities spread, a young doctor at the hospital in Pristina heard the story of a family who had lost a child in the war. It made her think of the little boy she knew as Lirim, the war orphan. The doctor contacted one of their cousins and told him of her surmise.

In the car on the way to the hospital this week, Afrim Rexhepi tried to suppress the hope surging inside him. "I was telling myself, until I go there and see him, I will not believe that this is my son," he said. Those doubts vanished with the utterance of the single word.[2]

Kastriot Rexhepi himself[3]

"Bab," Kastriot said to his father, which means "Dad" in Albanian.

Since their home in Kolic was destroyed, Rexhepiüfs family moved into an abandoned house in a slum in Pristina. Reunited with his parents, Rexhepi appeared entirely comfortable in his mother's arms in front of the journalist. Bukurie said, "I couldn't imagine a better ending."[4]

b. Mary Kellyüfs Opera The Ballad of Kastriot Rexhepi

The

Poster for The Ballad of Kastriot Rexhepi[5]

This story inspired Mary Kelly, a conceptual artist who teaches at UCLA, to create an opera called The Ballad of Kastriot Rexhepi with an Original Score by Michael Nyman. This work, the product of collaboration with composer Michael Nyman, premiered on December 11, 2001 at Santa Monica Museum of Art. Kelly knew Nyman since her early career in London. In London, her circle of friends also included Peter Greenaway, who had worked with Nyman, a composer famous for his film music, in making The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover. Nyman had also done the score for Jane Campion's The Piano, an international box-office hit. This installation represents the first time Kelly has incorporated music in her work.

Musically, Nyman said, "there are materials [in it] that are common to all four verses, a kind of refrain that is more or less the same, that separates the verses. But I think there is more dissimilar between the verses than similar. I found myself stopping after every line and making individual meaning and musical parallels [for] each line. That's brought out the best in me, not just the mechanistic sort of 'Michael Nyman writes a ballad' kind of thing. I sent Mary a fax saying this ballad has become a kind of anti-ballad.üh Kelly likes the notion of reconfigured balladry. "The way I wrote it doesn't follow a literary form," she said. "I did give him some compositional notes, but I'm sure he ignored them," she added, laughing.[6]

In this work, Kelly uses 49 grey panels of compressed clothes-dryer lint, arranged in the wave-like structure of sound transmission. They measure over two hundred feet and are wrapped around the gallery walls in an unbroken band. The experience of reading the text of the ballad linearly inscribed on the framed lint alludes to a 360-degree cinematic pan, as Kelly herself notes. Akin to a silent film, the work is completed by Michael Nyman's haunting 'soundtrack' for soprano and string quartet. Kelly also says, "It's not a fixed-piece performance. It's not music theater.ücIt's a score for an exhibition. That's the best way I can describe it."[7]

Kelly limits herself to black and white on this lint, she says, because she wanted to explain the notion of duration as something like a photographic sense, or that of an old black-and-white film, which is different from recent spectacle films, with the process of seeing the lint which contains the entire lyrics on 360- degree-surrounding walls. While the music is playing, she wanted to make the viewers feel the movement of psychic reality and physical reality by facing past history. Moreover, the instruments - the female soprano by Sarah Leonard and a string quartet - are both acoustic. By using non-spectacle live music, she tries to reproduce historical association and memory, which she admits is üguncomfortable to theorizeüh about.[8]

Installation View at the Cooper Union,

Details of the lyrics

As she writes, "and Kastriot, young patriot, says üeBab.üf" With his uttering of the Albanian word for father, the Ballad ruminates on the infantüfs speech as an inscription of national, familial, and sexual identity.

c. Her Psychoanalytic

Point of View

Her most characteristic works express some psychoanalytical point of view. In her earliest long- term project, Post-Partum Document (1973-79), Kelly investigated the intense and charged relationship between herself and her child. The work is made of six distinct sections that map and reconstruct the different elements of the relationship by means of remains, comprehensive charts, and narrative commentary. In this work, she interrogates the process of severance between mother and her child both in psychoanalytic ways and through advanced conceptual aesthetics.

In a conversation with Longhauser, Kelly explains what element of the Kastriotüfs story attracted her. Little Kastriot was separated from his family during the period when he would be starting to speak. According to poststructuralist psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, this time period coincides with the child's entrance into the symbolic order which creates the basics of language, and his acquisition of sexual identity, on which all other forms of identification (including ethnic identity) are founded. Upon being reunited with his parents, Kastriot's first word is reported to have been ügbab,üh which is Albanian for ügdad.üh In his case, the simultaneously recovered father and patronym illustrate the workings of the name of the father, the symbolic outfit of paternity. Because of a very confused ethnic position, Kastriot's survival was claimed as a symbol of Kosovo's newly found freedom.[9]

Kelly expects the history of human rights to be the subject of major debate in the twentieth-first century in the attempt to achieve enlightenment modernism for global civil society, an idea which first emerged in the French Revolution.[10] This word indicates her position on Kosovo, and her attitude towards the Ballad, which is not only happy, but philosophical and psychoanalytical. She had a weird impression when she read the story of Kastriot Rexhepi in the Los Angeles Times, which was accompanied with a photo of the mother kissing the cheek of Kastriot for the photojournalist Ami Vitale. This kissing can symbolically suggest new freedom in Kosovo, but at the same time, this is a show of Kastriot, as a young patriot, in front of media. Kelly also pointed out that the second name of the boy, ügLirim,üh means freedom in Albanian, which reflects the traumatized fear to survive for Albanian people in Kosovo. She also has a psychoanalytic point of view towards Kastriot, since facing death became so traumatic for him that it deprived him of his voice. This trauma was caused by the survival of facing the danger of death. This is not a happy- end story, but this is a part of the history in which it is important to think about global civil society.

d. Why in California and

New York, Not in Europe?

The Ballad was played in California and New York City which are in the United States. The problem is that the United Sates is the leader of NATO, and played an important role in bombing Kosovo. Therefore, this work has the dangerous implication of becoming the ballad of American triumph in Kosovo.

Christopher Miles describes Kellyüfs exhibition at Santa Monica Museum of Art in Artforum:

In a career defined by attempts to give physical form to complex language-based narratives, Mary Kelly has generally kept her work visually lean. Her installations tend to betray the aesthetic inheritance from the Minimalism and Conceptualism that defined her generation's coming of age. As a viewer, I have found myself at times wanting more--not because I wished the work were luscious or heroic (either would seem out of sync with Kelly's interest in psychological residue, trauma, personal history, identity formation, human interactions, and social hierarchies), but because I wanted it to catch my eye and hit me in the gut as much as it got me thinking. Well, I've learned my lesson. With The Ballad of Kastriot Rexhepi, 2001, Kelly has delivered a work that got me on every level and didn't let go.[11]

Miles then describes the material and the visual effect of the ballad, but he does not mention the psychological effects that Kelly was most concerned with.

The play at Cooper Union in New York City was almost the same. The viewers seemed to be attracted by the voice of the soprano, but not by the psychological effect that Kelly wanted to convey. The voice of the soprano is a medium that impresses people without reason. As a result, the voice of the soprano made this ballad a story of fantastic liberation of Kosovo by NATO.

As described in the Susan Sontag chapter, public opinion, which includes art critiques in the United States, is positive toward the bombing of Kosovo. This public opinion changes the meaning of the Ballad from a psychoanalytic work to one about the salvation of the Albanians by NATO.

Sanja Ivekovic also wondered why Mary Kelly did not mention her Ballad when Kelly met Ivekovic in Zagreb.[12] There is a possibility that Kelly was afraid of the criticism of her work in the former Yugoslavia, since Ivekovic is from the former Yugoslavia and is more familiar with the details of Kosovo and ethnic tensions in Yugoslavia than Kelly. This is a good example of how the meaning of works can be changed easily whether one is inside a particular nation-state or outside.

B. The Winner and the Loser in the Capital Letters of

HISTORY

a. Help the History - History is Always Written by Winners,

so We Need to Rescue the History

The war in the former Yugoslavia produced five states: Slovenia, Croatia, Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia and Montenegro. Kosovo, nominally a part of Serbia and Montenegro, has become an international protectorate managed by KFOR and the UN Mission in Kosovo.

A less nationalistic and more democratic government started in Croatia after the elections following Tudjmanüfs death at the end of 1999. In Serbia and Montenegro, a nonviolent revolution in Serbia in late 2000 overthrew Milosevic and replaced his regime with a democratic regime committed to a peaceful resolution of the regionüfs problems. In June 2001 the Serbian government extradited Milosevic to the ICTY to face trial. However, Milosevic won a seat in the parliament as a member of an ultranationalist party in December 2003.

After this war, all areas except Slovenia have faced long-lasting economic, social, and psychological depression. However, the saddest thing is that because of this war, these Slavic peoples cannot be citizens of the same nation again in the future. Because of the war, they try to keep their own identities under the name of different nations and religions.[13]

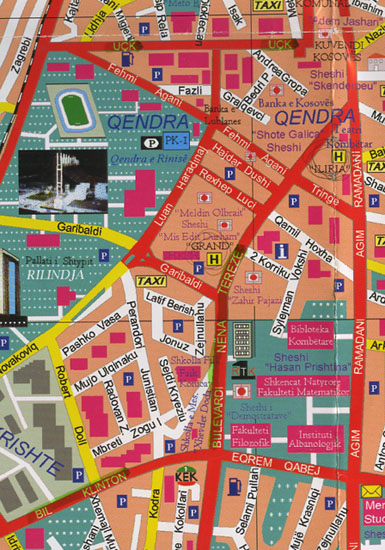

Map of Central Pristina, Capital of Kosovo

The unresolved final status of Kosovo and Bosnia was the source of continued regional instability and potentially of new armed conflicts. After the war, the cityscape of Pristina, the capital of Kosovo has been changed. There are streets called Bill Clinton Street and UCK (KLA) Street. The street "Marshall Tito Street" was renamed to Mother Teresa Boulevard (Bulevardi Nena Tereze.) On Mother Teresa Boulevard, there is a statue of Mother Teresa which was donated by an American peace group.

Statue of Mother Teresa on Mother Teresa Boulevard (Photo by Shinya Watanabe)

Mother Teresa was born in 1910 in Skopje, a child of ethnic Albanians from Kosovo. However, her statue was not welcomed in Pristina, since she is Albanian but Eastern Orthodox. The peace organization might think that the Kosovar people would love the statue, but this organization probably did not realize the complicated background of Kosovar Albanians because of media controls that did not report the religious background of Albanians.

The formal history is always written by winners. However, there are many people who are not properly evaluated by these winners, since they were on the side of weak people and succumbed. In the case of the wars in the former Yugoslavia, some people opposed the nationalist regime, and because of this, they were erased from formal history. Regarding the NATO bombing, the intellectuals who were against it were less evaluated after the victory of NATO. The job of the art historian is to rescue these people, such as Walter Benjamin has said.